A lover of baseball since the age of 3, my affinity for the sport ratcheted up when I began tee ball, and it increased even more once I began my career on 85th and King Drive in South Side Little League’s “Minor League,” for baseball players in the age range of 7-9. After moving on to “Little League,” for 10-12 year-olds, and then “Senior League,” for 13-15 year-olds, I became a member of my high school’s varsity baseball team as a sophomore. “Traveling” baseball during the summer was basically a mandate in my household, so outside of Senior League play (by this time, for Hyde Park Kenwood Little League), another 30-40 games were on my schedule. I never noticed that as I had gotten older, the number of Black teammates I had decreased. It didn’t dawn on me that this was viewed as an epidemic of sorts by some scholars, historians, and journalists. Unfortunately, I ultimately figured this was the norm: If you’re Black and stick with baseball after the age of 12, Black teammates would be nearly as scarce as Nicki Minaj fans in a library on a Saturday afternoon. Oddly enough, it didn’t feel all that weird to look at my teammates and see nothing but White faces.

While any team I played against was a rival, there was one particular adversary that really spoiled my milk as a kid: Jackie Robinson West Little League. We only played them in the district tournament, and usually it was in the championship game. Undoubtedly, “JRW” and South Side were the two best Little Leagues on the south side of Chicago, as evidenced by the fact that the two leagues played each other in both the 9-10 and 11-12 year-old tournament championship for five years straight. And while it was fun to play in the championship game, it wasn’t fun to lose. Every year. Sometimes, by an embarrassing margin. Simply put, Jackie Robinson West was always better than us, in just about every facet of the game of baseball.

It was a complete shock to learn that although South Side, JRW, and other all-Black Little Leagues like Rosemoor and Jesse Owens produced many talented baseball players, our community wasn’t seen as one that particularly cared about the sport. Some of that could be attributed to the ignorance of people who couldn’t fathom a group they perceived to be dim-witted and only interested in showing off their athletic prowess, to love a sport that has so often been called “a thinking man’s game.” We were “supposed” to play basketball or football, but not baseball. And if we did play baseball, we certainly didn’t take it seriously, because our future in athletics didn’t lie in that sport.

So holy hell, was I happy to see JRW playing in the 2014 Great Lakes championship game not even two weeks ago. I actually expected them to win, but just getting there was a huge accomplishment in its own. To see them come away victorious and do just a little to dispel the stereotypes that Blacks don’t care about baseball, all the way down to the youth, brought me immense joy.

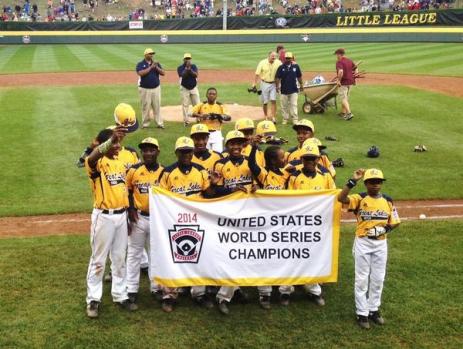

Appearing in the Little League World Series in Williamsport, PA, would have been “enough” for me. Then again, if I were a member of JRW’s team, anything less than winning the entire tournament would have been a failure. Hitting. Pitching. Fielding. Throwing. Running. This JRW team had those five tools in their collective tool belt, and used them greatly as they won and won some more, beating Mo’ne Davis’ Taney (Philly, stand up) Little League team before beating a team from Las Vegas to be crowned United States champions. Sure, the task of beating South Korea in the Little League World Series title game, a team that had already won the Little League World Series twice before, was a tall one, but by this point I figured JRW was a force to be reckoned with. Despite the plentiful support from fellow Chicagoans, as well as a few prominent Black Major Leaguers, South Korea ended JRW’s dream run, beating them 8-4. Still, I’d like to believe the kids from JRW have acquired an absurd amount of juice because of their journey.

Who knows if what JRW accomplished will draw more Blacks to the sport. When Tiger was dominating golf in the late 90s and early 2000s, I assume that Black membership in golf increased, but probably not enough to be viewed as a revolutionary wave of new golfers. Venus and Serena Williams were not only good from the beginning of their respective tennis careers, but they brought much-needed flavor to a sport that had always been vanilla, figuratively and literally. Still, while one would probably not be able to argue that there wasn’t an increase in Black membership in tennis after the Williams’ rise to popularity, the average tennis camp would be predominantly White, I’m just assuming. Watch an NCAA tennis match and try to feign surprise when you see essentially an all-White squad, or one with no Blacks on it. Even when it comes to “counter-culture” sports such as skateboarding, black skater Stevie Williams’ success hasn’t exactly gotten many Blacks outside of his neighborhood and surrounding ones to follow his tracks to pro skating.

I do know that the media, both mainstream and underground, does a great job of demonizing and criminalizing young Black males in America, especially those who reside on the south side of Chicago aka the “inner city.” I do know that the JRW players owned this summer, despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of us weren’t thinking of them just three weeks ago. I do know that there is at least one example to point to when a person questions whether young Blacks are interested in baseball anymore.

Baseball, a sport somehow still seen as our nation’s pastime, is ready for JRW. It should be, at least. And if it’s not, JRW or a team like it should just bust the damn door down, anyway.